Blackout

Location and Working Hours

Bárbara de Braganza 9, Madrid. Open daily 11:00-19:00 Monday and Sunday ClosedCurators

Paula Anguita.Blackout: Paula Anguita

Our idea of reality has varied throughout history and each variation has expanded art into new languages. One of the central axes in Paula Anguita’s work is the exploration, based on optical strategies, of new points of view that manage to represent the model of reality in which we live.

In the Middle Ages, the size and location of characters within a painting was established by their symbolic relevance. In the Renaissance, trying to reproduce a more faithful image of reality, a vanishing point was incorporated in the center of the painting, like Copernicus’s model, with a sun in the center of the planetary system. Kepler’s ellipsoid model led the Baroque to create oblique perspectives. And centuries later, while Einstein developed the theory of relativity, moving away from Euclidean geometry, Picasso distanced himself from classical perspective, rearranging faces and objects in multiple perspective. Both, simultaneously, understood that reality depended on the relative position of the observer.

What is the most appropriate perspective to represent the current observer’s position? Anguita has explored that question by modifying the spectators’ point of view towards a work. First she used the Fresnel technique, a plane folded like an accordion that displays a different image from each end. Thus, in the words of Anguita, the viewer could “compose and decompose the image at will through their own displacement, breaking the frontal staticity typical of the painting format.”

Her next experiment was the light boxes that, in this exhibition, we can see in the work Mother and Son. The boxes contain analog images that are illuminated with LEDs, producing the sensation of being in front of a digital device. The transition to which the viewer is forced by the format of the light boxes is related to the images they contain. In this case, the image is that of a Victorian-era mother, holding her dead son, who is fading in a ghostly glow.

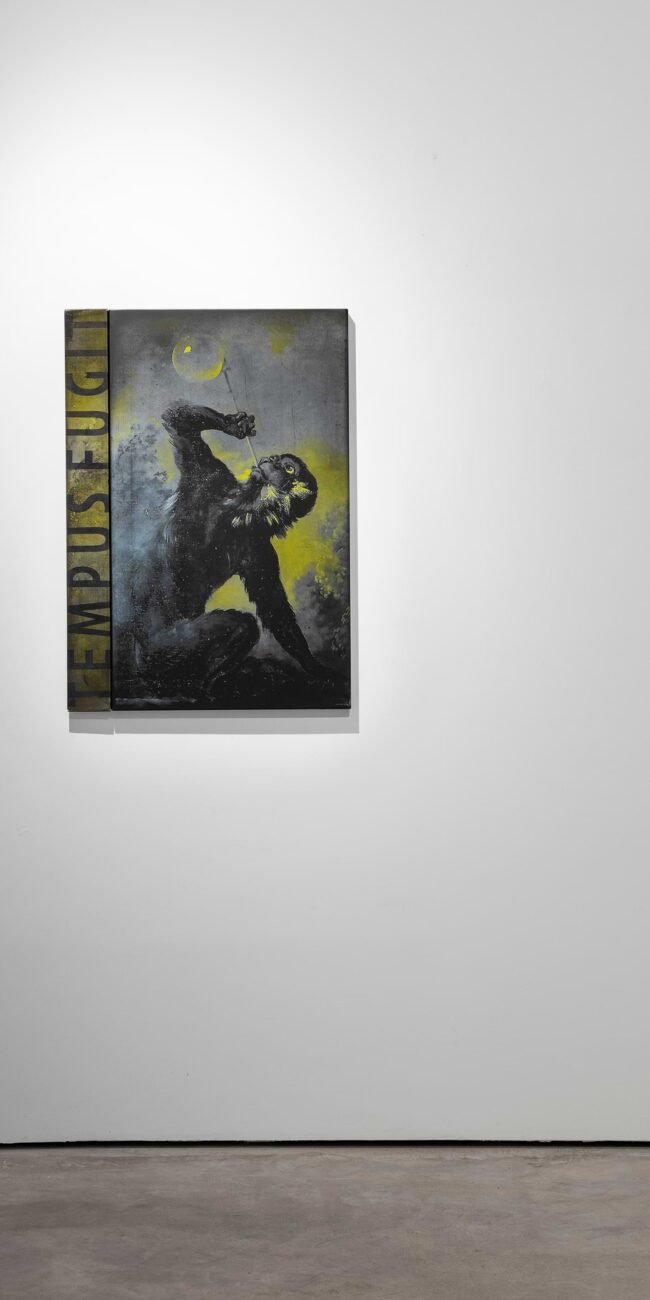

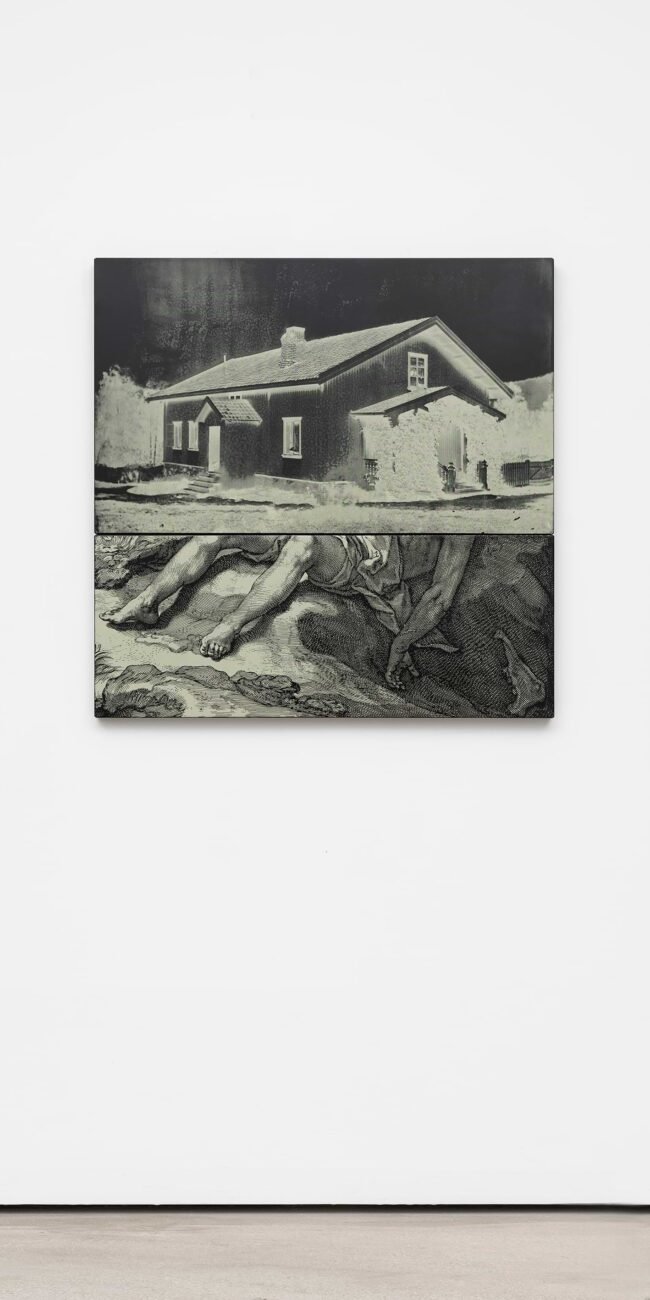

During the mental lockdown of the pandemic, Anguita had an epiphany. Suddenly, an equation appeared to her, the sum of two materials, whose optical properties would allow two different images to be displayed in the same space. She called it Double Vision: a surface that, when photographed with a flash, reveals a hidden image. It is an extraordinary metaphor for our current point of view: clinging to the phone as a prosthesis that articulates our existence, living in two realities, in the one that we observe, less and less, outside the screens and in that selection of the digitized reality that we obtain through our phones. Anguita has created analogous works that we can only see complete through the digital image, like our present reality, built from these two formats.

In the Salomé series we are faced with eight black, neat rectangles, without reflection. It is inevitable to remember Malevich’s black square, however, the Russian artist’s rejection of figuration disappears when we observe the work from our phones. Then that blackness that evokes nothingness, emptiness, death, suddenly fills with movement and vitality on our screens, with women who dance to the verses Prayer to Life, by Salomé, in which the Russian psychoanalyst she declares love for life, its joys and afflictions. Anguita found the women who seem to dance in the archive of a French psychiatric hospital from the late 19th century; They were inmates diagnosed with hysteria.

In Fatal Attraction, Anguita superimposes the equations to calculate the free fall of a body, on top of the photograph of Evelyn McHale, an accountant who, at the age of 23, jumped from the 88th floor of Empire States and fell onto a limousine. In the balcony of the building she had left her coat, neatly folded, along with a note that began by saying: “I don’t want anyone inside or outside of my family to see any part of me.” However, a young reporter who heard the impact ran to take the photograph. The contrast between Evelyn’s tragic outcome and the serenity of her face, the apparent comfort of her body on the roof of the limousine, the position of her gloved hand holding her pearl necklace, produced a moving effect. Life magazine published it with the headline: “The most beautiful suicide.” Warhol made a silkscreen that repeated the photograph sixteen times and included it in his Death and Disaster series, as a criticism of the media’s spectacle of tragedy. Anguita, on the other hand, contrasts Evelyn’s unfortunate end with a scientific coldness, lacking story and feelings. Fatal Attraction is, simultaneously, the impassive beauty of the accountant and the attraction of the gravitational force that ended her life.

Death is a theme that haunts Anguita’s works, as if repeating memento mori in our ears. It reminds us of the transience of life, not to highlight the anguish faced with the inevitability of death, but, on the contrary, to allow, as Salome says in her Prayer, for the spirit to burn in the flame of life. It’s the flash, before the blackout.