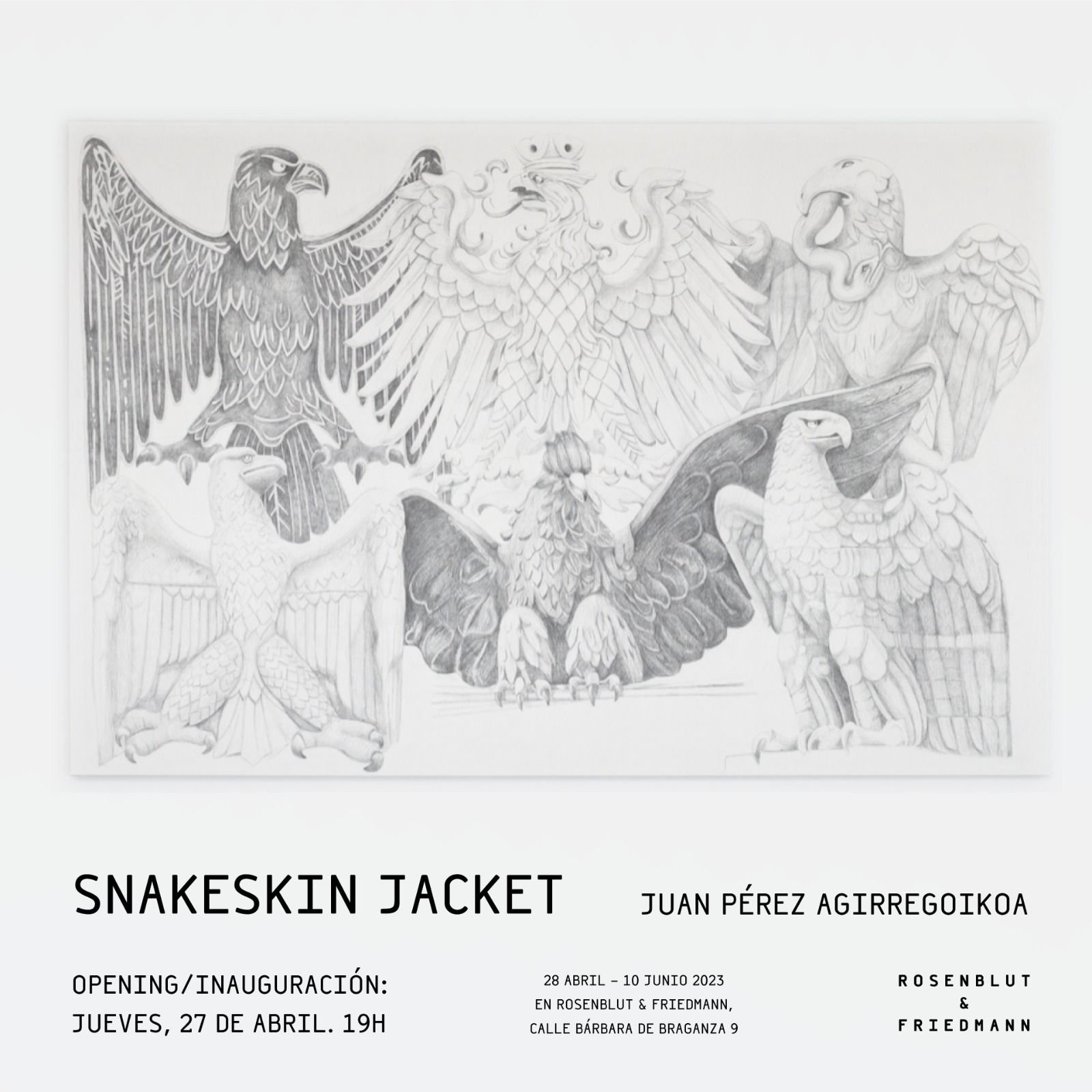

Snakeskin Jacket

Location and Working Hours

Bárbara de Braganza 9, Madrid. Open daily 11:00-19:00 Monday and Sunday ClosedArtists

Juan Pérez AgirregoikoaSnakeskin Jacket: Juan Pérez Agirregoikoa

What is the purpose of art? For Juan Pérez Agirregoikoa: to put an end to culture. Not with the entirety of culture, since he knows that revolutions that forget ancestors, sooner or later, end up in the hands of others who are equal or even worse. His artistic struggle is, therefore, against those aspects of culture that we adopt and pass on from generation to generation without questioning, without subjecting them to common sense; myths and judgments that are imposed on us from a young age, such as religion or the nation, until they become the essence of our identity. Pérez Agirregoikoa takes the symbols of culture that operate as social glues and, by modifying the framing or the technique, subverts their meaning and exposes the absurdity that is hidden beneath them. The result is not without humor. “Steven Segal is violent but very good,” says one of his banners.

This purpose of art, however, is only the starting point. For Pérez Agirregoikoa, the big question an artist must face is how to portray what they mean. At the beginning of his career, he used only one language but, very soon, he considered it limiting and concluded that each idea required a different technique. That is why among his works are oils, watercolors, charcoal, videos, pop-up books, banners, canvases carried by planes, mediums that he meticulously chooses, after an arduous creative process that he compares to a long digestion. “When the problem is resolved, the waste, the rest of it, is what remains of this process, what detaches from the body, which in our environment is called art. Art would be a great production of waste.

The works that he presents in this exhibition are “the remains” of an investigation of what is happening around him: the rise of extreme right-wing mass movements. They are works that dilute the symbols of power, like the hands raised in the Nazi salute, which looks like a collage made by a child who still doesn’t know how many fingers a hand has and who has fun illustrating horror.

The “Great Black Chickens” series are large, imposing canvases, mounted high up, forcing us to look up to see a set of eagles (drawn in pencil) from different cultures (in this case, eagles from ancient Rome and of fascist Rome, of Germany, Russia and the United States). In ancient times, the eagle was associated with the gods of power and war, symbolizing that which dominates from above and that, with its penetrating gaze, is capable of seeing everything that happens below it. By gathering all these eagles in the same frame, their petulance is enhanced, as if each one were striving to appear more majestic than the other, as if they were posing for a selfie, looking for the exact angle that highlights their most imposing features, the imposture of the heroic, of virility, the fantasy of being a pure symbol of patriarchy when, perhaps, they are nothing more than “big chickens.”

In the series “The American Imperialism is…” we see tigers —another symbol of power that is, in turn, a predatory animal— built with small pieces of colored paper, like a children’s collage. It is the plastic representation of a concept that Mao Tse Tung used to describe North American imperialism. According to Mao, the reactionary forces of that empire seem terrifying but are like a “paper tiger” because they lack real power when they are not together with their people. Seven decades later, Mao’s sentence sounds childishly naive.

The work “History of the snakeskin jacket” is built like a comic, divided into ten vignettes, in which a new version of the food chain of the animal kingdom is displayed. The ant eats a leaf, the spider eats the ant, the toad the spider, and so on until we come to the elephant that is not eaten, but hunted, like a trophy, by none other than King Emeritus Juan Carlos I. However, the ex-king is not at the top of the food chain, as it is eaten by a boa. The image of the boa with the undigested king emeritus inside (which must seem indigestible to Pérez Agirregoikoa) reminds us of the beginning of The Little Prince, by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, where the narrator makes a drawing of something that looks like a hat but is actually a snake that has swallowed an elephant and, in this case, since the former king has killed the elephant, then so the boa has eaten him. The boa is not the last link in the chain either and, although it is not eaten, it ends up being transformed into a jacket. And it’s not just any jacket. In the movie Wild at Heart by David Lynch, there is a scene where Lula (Laura Dern) picks up Sailor (Nicolas Cage) from jail. Seeing him, she kisses him and hands him a snakeskin jacket. Cage puts it on and asks, “Did I ever tell you that this jacket represents a symbol of my individuality and my belief in personal freedom?” This is where the name of this work and this exhibition comes from. Is individualism at the top of the food chain? Are these works an expression of Pérez Agirregoikoa’s personal freedom, his snakeskin jacket? The answer is not clear, because in his attack on culture, Pérez Agirregoikoa dismantles the possibility that there is only one reading, as the symbols that he subverts would make us believe.

Dead Letter

In our video room, the artist exhibits the video ¨Dead Letter.¨

Dead Letter (letra muerta, en castellano) is an expression used to refer to a “text that has no more value or authority” and figuratively means “something that is left without effect, that has no more power”. In 1964 Pier Paolo Pasolini made a version of the Gospel according to Saint Matthew that is considered the most faithful reproduction of the life of Christ. Juan Pérez Agirregoikoa, surprised by the fact that Pasolini had not included in his version any of the verses dedicated to economic issues from the Gospel of Matthew (who was a tax collector and can be considered one of the first theorists of capitalism ), decides 50 years later to make a short film with the missing parts, like the parable in which the investor who succeeds is rewarded and the one who does not obtain benefits is punished. The film takes up the formal and aesthetic elements of Pasolini’s film, shot on the outskirts of Sao Paulo, and stages the passages omitted by the Italian filmmaker.